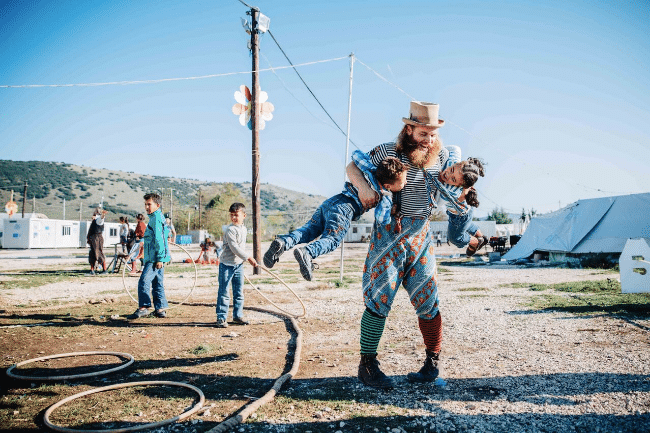

Helping kids in refugee camps

Lead by founder and CEO Ash Perrin (or Bash, when he’s in the baggy pants), the Flying Seagull Project has been spreading a gospel of laughter and joy to some of the world’s neediest children since 2008, helping kids in refugee camps.

“There are more than 50 million child refugees worldwide. Their needs are complex. They might have seen terrible things, experienced awful hardship, been torn away from their family, maybe travelled alone. They often lack the social structures that would usually help them through challenging developmental stages. Our job is to provide respite from the suffering, to use laughter to alleviate the burden of premature adulthood, to let them be children again—if only for a fleeting moment.”

“It isn’t a matter of whether we can change the world; it is a matter of how many children’s lives we can improve. There is more that unites us than divides us.”

Where did the idea for the Flying Seagull Project come from? Tell us a bit about how it came to be.

I went to drama school and had worked as a professional entertainer for many years. But there was always that sense that perhaps I could be doing something more with these skills I’d been privileged enough to develop. In 2007, I was on a backpacking holiday to Cambodia when I found myself playing guitar and doing some magic in an orphanage. The children were comfortable and happy, but it struck me that these were feelings they didn’t usually experience. I realised that as an entertainer, a clown, who cares passionately about the health and happiness of children, I should do as much as possible to spread love, light and laughter to those who need it most. I wrote the idea for the Flying Seagull Project on a piece of paper that night, and launched it three months later.

How much of a struggle was it to get the project up and running?

Starting a charity can be pretty intimidating, but I was lucky to have help right from the start. Naomi Briercliffe, Matthew Willis and Penny Lyle—old hometown friends of mine—were immediately on board and came with me on the first tour: a trip across Romania in a beaten-up old transit van. I ponied up £3,000 of my own cash and raised another £4,000 from family and friends, and we spent a couple of months driving from Oradea to Bucharest, stopping in at orphanages, hospitals and charities along the way. The Flying Seagull Project has grown every year since then, in terms of both the number of volunteers and the number of children reached, yet we are still very much a grassroots organisation.

You’re now doing a lot of work in Europe’s refugee camps. Did you find much resistance from camp administrators—or even from the refugees themselves?

You have to do a fair bit of admin to gain access to the camps, but we have all the necessary paperwork and are very familiar with the processes by now. We try to build constructive relationships with all interested parties; we were one of the last two organisations allowed to stay at the Idomeni camp in Greece before it was shut down. I’m very proud of that.

Every place is different, but kids are the same all over the world. They can be wary early on, their faces hard. But once they get used to our presence, you see them open up and recognise us for what we are. It helps that our big-top tents fit in with the tents in the refugee camps, so it’s easier to be accepted as friends and members of the community. And because we’re clowns, we’re not seen as being an authority, so we’re not intimidating. Our shows work without language, so there’s no barrier to entry. We have no other agenda than to share a good time, and sooner or later that comes through.

What does a Flying Seagull performance look like?

We do all kinds of things—music, arts, dance, clowning—but it is always very loud and colourful, a chance for the kids to let off steam, to be silly in a good way without getting told off. We keep things simple, working with sound and movement to ensure we’re communicating with all the kids, and basing our games on circle structures so that everyone is treated equally.

What’s it like inside the camps?

We’ve been going to camps for nearly ten years now. The conditions vary, but amenities are basic at best; imagine a never-ending camping trip, except less enjoyable. I wish there weren’t a need for us to do what we do. Kids shouldn’t be in refugee camps—but they are, and as long as they are, we’ll be here too.

What does the Flying Seagull Project look like these days?

Over the last decade, we’ve done more than 3,000 shows for more than 80,000 kids, but we are still a small charity. We only have about twenty entertainers, but they are all exceptional, highly skilled and passionate performers. We go where we think we can make the biggest difference, and we work hard. In Idomeni earlier this year, we saw 1,000 children a day, every day, for seven weeks. They would see us arriving on our unicycles, or hear our trumpets, and come running towards us, singing and dancing. In late September, we embarked on our sixth mission to Greece in the last eighteen months, starting in Lesvos, off the coast of Turkey in the north-eastern Aegean Sea. The conditions here are among the worst we’ve seen—which makes our work feel even more important.

What are some of the particular challenges you face as performers in this sort of environment?

According to the UN, there are more than 50 million child refugees worldwide. Their needs are complex. You have to bear in mind that they might have seen terrible things, experienced awful hardship, been torn away from their family, maybe travelled alone. In the camps, they often lack the social structures that would usually help them through challenging developmental stages. They are also used to being treated with suspicion and hostility, which can exacerbate other problems. Our job is to provide respite from the suffering, to use laughter to alleviate the burden of premature adulthood, to let them be children again—if only for a fleeting moment.

Why is something like the Flying Seagull Project so important?

Because happiness matters—yours, mine, everyone’s. As well as food and shelter, these children need a safe space to relax, laugh, sing and dance. Play is so integral to a child’s development, and a lot of these kids have so little chance to just fool around and be kids. We’re not claiming to be miracle workers, but we try and offer them so much fun that they cannot help but join in.

What are your hopes for the future of the Flying Seagull Project—and for the families you work with?

More of the same. It isn’t a matter of whether we can change the world; it is a matter of how many children’s lives we can improve. There is more that unites us than divides us, so join the laugh-olution and make the world a better place.